Four Generations at Work: The Unexpected Truth

There has been a lot of attention paid to the increasing number of generations currently in the workforce. From the tech-savvy and ambitious Gen Z-ers to the more analogue and experienced baby boomers, with Gen X and millennials in between, the differing needs of the generations have been a hot topic in the world of learning and development.

Wiley Workplace Intelligence sought to get to the bottom of how one’s generation informs their experience at work. Do these differing areas of skill and interest cause conflict? Or does the wide breadth of influence and expertise have the potential to come together to create more powerful, diverse, and cohesive organizations?

Let’s dig into the research. We surveyed 2010 people to understand more about the generational makeup of the current workforce and how each group experiences life at work. The results were surprising. While we found that there were reported differences between the generations, in most cases they weren’t as vastly different as one would think. In fact, the picture we got from our research is that despite all the hype we are a lot more alike than we may think. Read on to learn what that means for you and your organization.

The Generational Makeup

Our respondents (53% of whom are people managers) were asked to select which generation they belonged to based on their birth year. Millennials (also known as Generation Y, but for the purposes of this article will be referred to as the more commonly used term millennial) and Gen X make up the majority of the workforce with a combined total of 84%. This majority makes sense as many baby boomers have already entered retirement and the younger members of Gen Z have not yet joined the workforce.

Mental Health Concerns Impact Gen Z and Millennials Most, Baby Boomers Least

Having come of age in the post 9/11 world and not knowing life without the internet, Gen Z is growing up in a uniquely different era than earlier generations. While it is hard to define the specific cause, the dominance of social media, economic and global instability, and a worldwide pandemic during their formative years may play a role in the 29% of Gen Z employees that reported their mental health impacted their ability to perform their work a moderate-to-great deal. Millennials were not far behind with 23% reporting a moderate-to-great impact on their ability to perform their work.

A whopping 77% of baby boomers responded “not at all” when asked if their mental health impacted their ability to perform their work. While it would be easy to assume that the older generations feel less societal pressure and have more stability due to their age and status thus reducing their likelihood of mental health struggles, that can’t be certain. Older generations were also raised with different norms around sharing emotions and the discourse around mental health was not as common which could potentially impact their comfort around sharing this kind of information.

Gen Z and Baby Boomers Report Higher Levels of Hostile Work Environments

Interestingly, both Gen Z and baby boomer respondents reported that a hostile work environment impacted their ability to perform work equally at 24%, followed by millennials at 22%. Common drivers of a hostile work environment are a lack of communication, destructive conflict, poor work/life balance, and a lack of trust between colleagues.

While Gen Z and baby boomers reported having the most experience with hostile work environments, all generations ranked within a five-point range. This speaks to the fact that addressing common workplace struggles that lead to burnout and hostile work environments can go a long way in creating better organizational cultures.

Older Generations Report the Strongest Desire for Meaning at Work

Despite some of the stereotypes about younger generations and their often-lofty idealism, our research showed that surprisingly, Gen X and baby boomers reported the highest levels of priority around having a personally fulfilling job versus a job that pays well.

While the older generations reported the highest numbers, the majority of all respondents said they agree-to-strongly-agree that personal fulfillment at work trumps a big paycheck. Creating organizations that encourage accountability, trust, and allow everyone to be a leader regardless of their role or title, can go a long way to creating meaning at work. When individuals are treated as more than cogs in the wheel of business, they will be more inclined to find fulfillment, no matter their age.

Middle Generations Are the Driving Force Behind Work/Life Balance

While work/life balance has been an area of focus for many organizations over the past few years, the highest numbers of Gen Z and millennials reported having a job that prioritizes work/life balance is essential.

This may be for a number of reasons but is most likely due to the factors that give this age group the moniker “the sandwich generation.” Many in this age group are caring for both aging parents and children simultaneously, demanding that their attention be focused on multiple places at once. For this group work/life balance is not only a nice-to-have, but a necessity as they manage their home lives and careers.

All Generations Report Feeling Understood by Each Other

Incredibly, the vast majority of respondents reported feeling understood by colleagues of all ages. While there are obviously differences in the way that each generation was raised, from the world events that shaped them to the cultural understanding around work norms, our research points to a large amount of understanding between the generations, with Gen Xers topping out at 93%.

This is an amazing insight, and perhaps surprising, given the noise that has been made about the differences between generations at work.

Whatever generation you belong to, this research assures that while we all may have slightly different styles and priorities that we largely have more in common than we may think and given the right tools organizations can bring this cohesion and understanding to the next level.

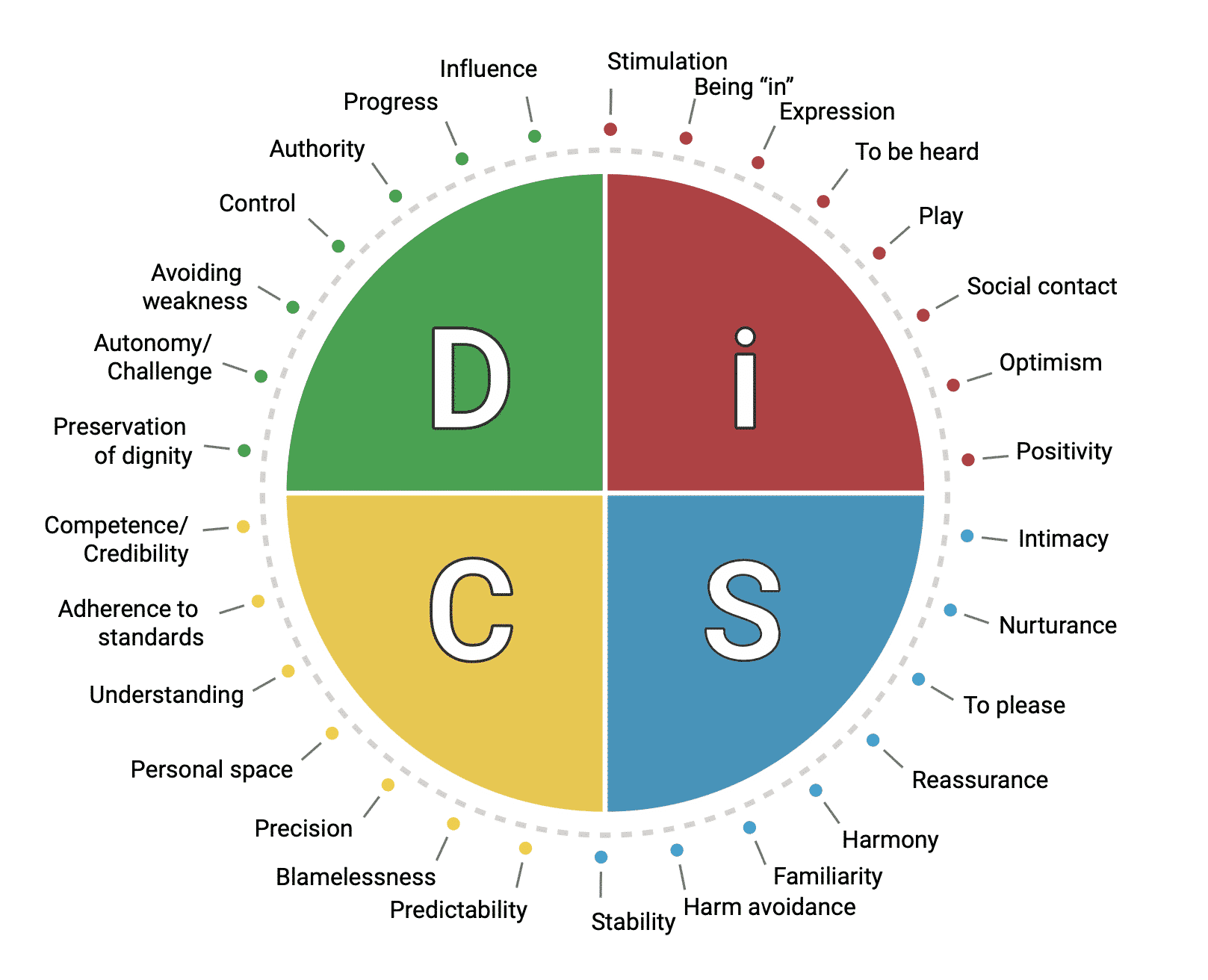

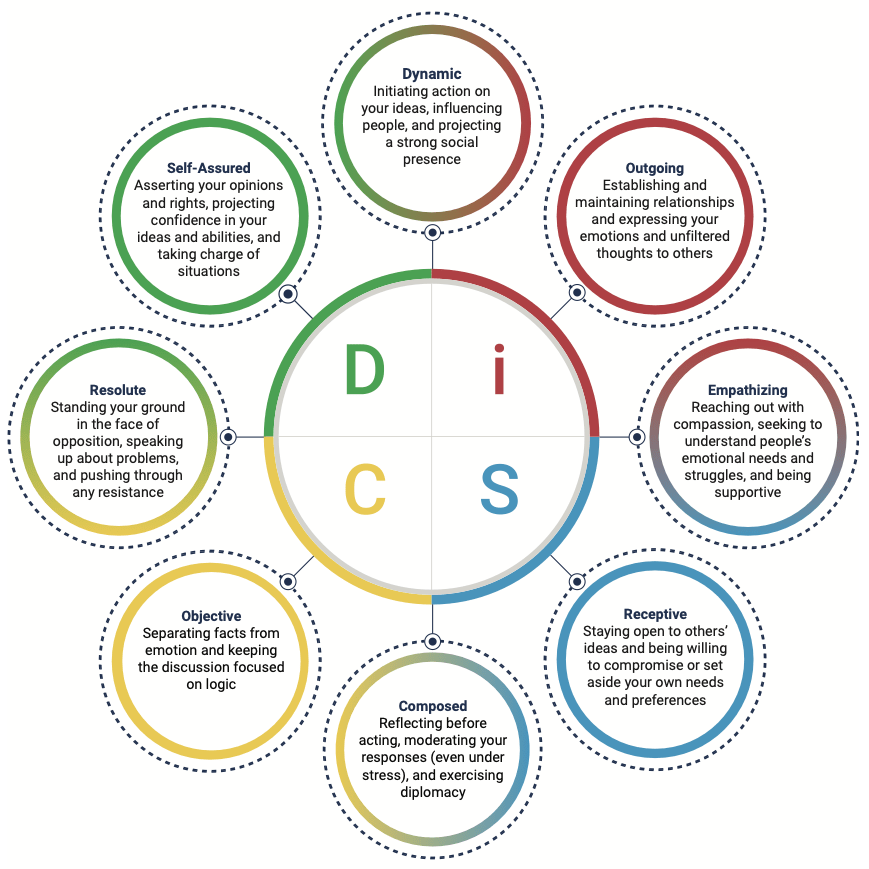

Whether it is with facilitated learning experiences designed to help your people better understand themselves and others, or team building exercises that build trust and teamwork, organizations can create positive experiences, with meaning, for employees of all ages.

This blog content belongs to Everything DiSC, a Wiley brand.

You might also be interested in